Article in World Pipelines - An Energy Balancing Act

Boryana Nedyalkova, EMIS Researcher, highlights the crossroads that Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) is at regarding its energy landscape and the careful balancing act between hydrogen vs methane.

The Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) region is at crossroads as it reshapes its energy landscape in the aftermath of severed ties with Russian gas. Recent infrastructure investments have diversified gas flows and boosted access to LNG, but the EU’s long-term decarbonisation agenda also demands a parallel shift toward hydrogen. This has stretched the CEE countries between managing the immediate challenges of

energy security and preparing for a hydrogen-driven future. /1/

CEE between molecules

Natural gas supply diversification is triggered by the EU announcing plans to phase out Russian fossil fuel imports by 2027, pushing a ban on new pipeline contracts starting 1 January 2026, and ending imports under existing short-term contracts by 17 June 2026. /2/

Working towards a gradual shift to green hydrogen is, in turn, mandated by the EU Hydrogen Strategy that has set binding targets for 10 million t of domestic electrolyser capacity, used for green hydrogen production, and 10 million t of renewable hydrogen imports by 2030. /3/

As a result, hydrogen projects have slowly been gaining momentum across the 27-nation bloc. While more than 90% of low-emissions hydrogen projects in Northwestern Europe remain in early phases of development, /4/ on 1 August 2025, the European Commission (EC) launched its third auction in support of renewable and low-carbon hydrogen projects that demonstrate technical and financial readiness. /5/

CEE countries successful in aligning their technical, regulatory, and financial planning with the Brussels-driven

pace of development, will be in position to achieve a strategic place within this new ecosystem, while laggards will risk losing funding, alongside remaining locked into carbon-intensive infrastructure while EU incentives and focus shift to alternative sources of energy.

Yet, the EU’s visionary hydrogen policy is complicated to say the least. On one hand, it strictly defines green hydrogen as one obtained from renewable energy and not fossil fuels, and prioritises the financing of such projects, also planning the construction of an EU-wide hydrogen transportation infrastructure. On the other, it envisages a transition period where hydrogen is to be obtained from fossil fuels and mixed with natural gas; and transported on the current gas pipeline network, following costly upgrades to technically accommodate the hydrogen-methane mix.

This makes EU’s hydrogen plans a challenge to implement in the CEE context of legacy energy systems and other structural, economic, and institutional constraints. Issues range from regulatory complexity and lack of infrastructure readiness against tight deadlines, to lack of national industrial hydrogen targets, and alleged disconnect from market reality against high implementation costs.

Uneven midstream hydrogen readiness

Technical compatibility

One aspect of hydrogen readiness is the technical compatibility of the gas networks of CEE countries (Poland, Czechia, Slovakia, Hungary, Croatia, and Romania) for handling hydrogen blends (allowed until the end of 2029) /6/ or pure hydrogen safely and efficiently. This is because the countries have been mapped along the future routes of the five EU hydrogen corridors, made up of both repurposed and newly built pipelines, and defined by the European Hydrogen Backbone (EHB) in May 2022. /7/ However, as of mid-2025, the CEE countries’ plans related to corridor implementation remain vague, risking stalling project progress if other EU member states advance on schedule. Slovakia’s Transmission System Operator (TSO) Eustream, /8/ Hungary’s FGSZ, /9/ and Romania’s Transgaz /10/ have reported testing hydrogen blending against a lack of set EU standards on the proportion between natural gas and hydrogen in the required blend. /11/ In March 2024, Poland’s Polska Spółka Gazownictwa (PSG) obtained the country’s first technical certificate for up to 20% blended hydrogen transportation, on the Jelenia Góra-Piechowice pipeline. /12/ Czechia and Croatia have not publicly disclosed blending trials yet. Not all existing infrastructure (pipelines, valves, and compressors, amongst others) can handle any blend proportion, which adds a further level of uncertainty to the technical compatibility required. /13/

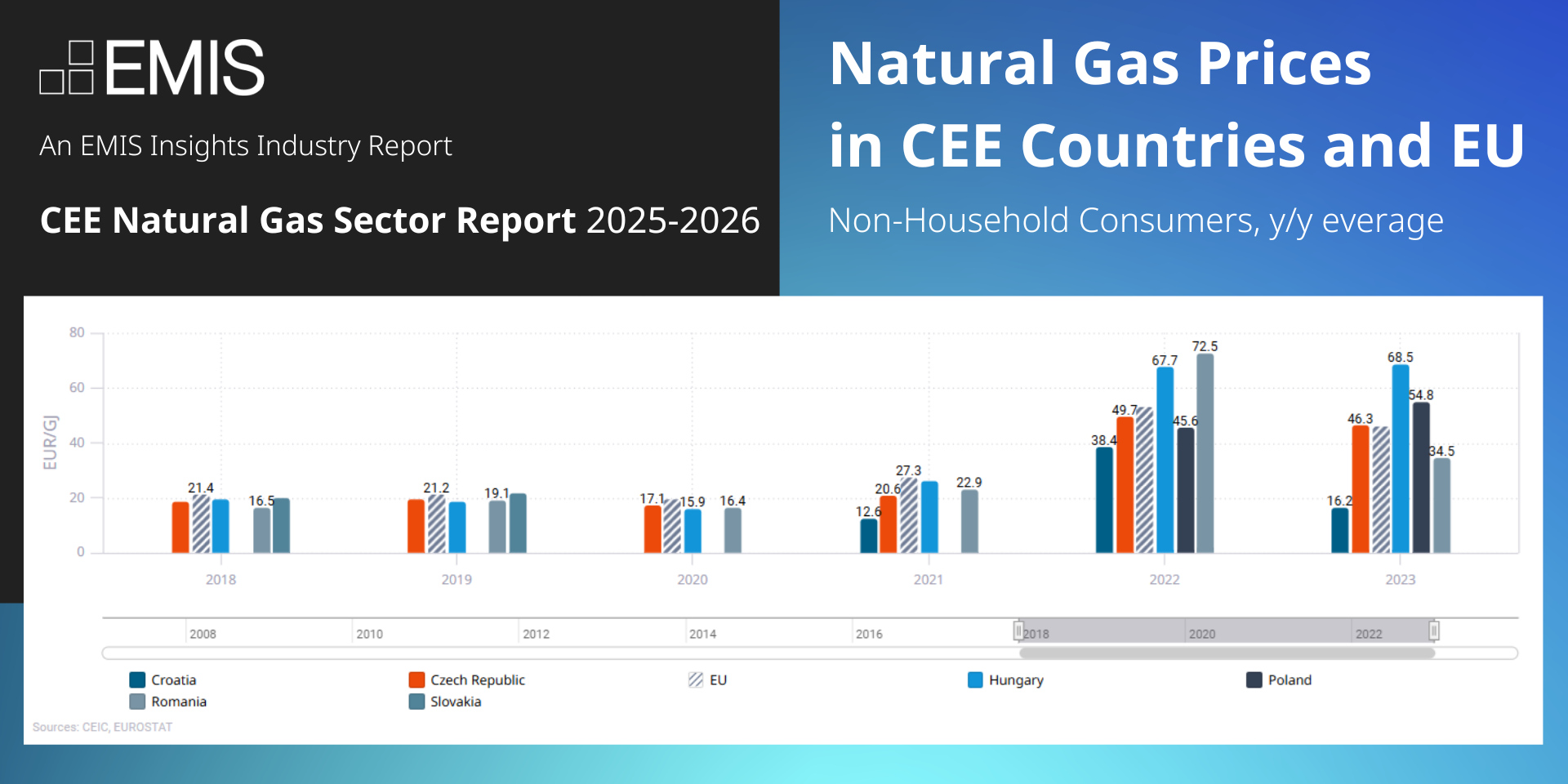

Figure 1. Natural gas prices in CEE countries and EU (non-household consumers, y/y average).

Post-2021 gas price surges hit CEE economies the hardest at the industrial consumer level, driving up production costs and inflation, while government interventions in several countries muted the impact on household gas prices.

* For more data - check the EMIS Insights CEE Natural Gas Sector Report 2025-2026.

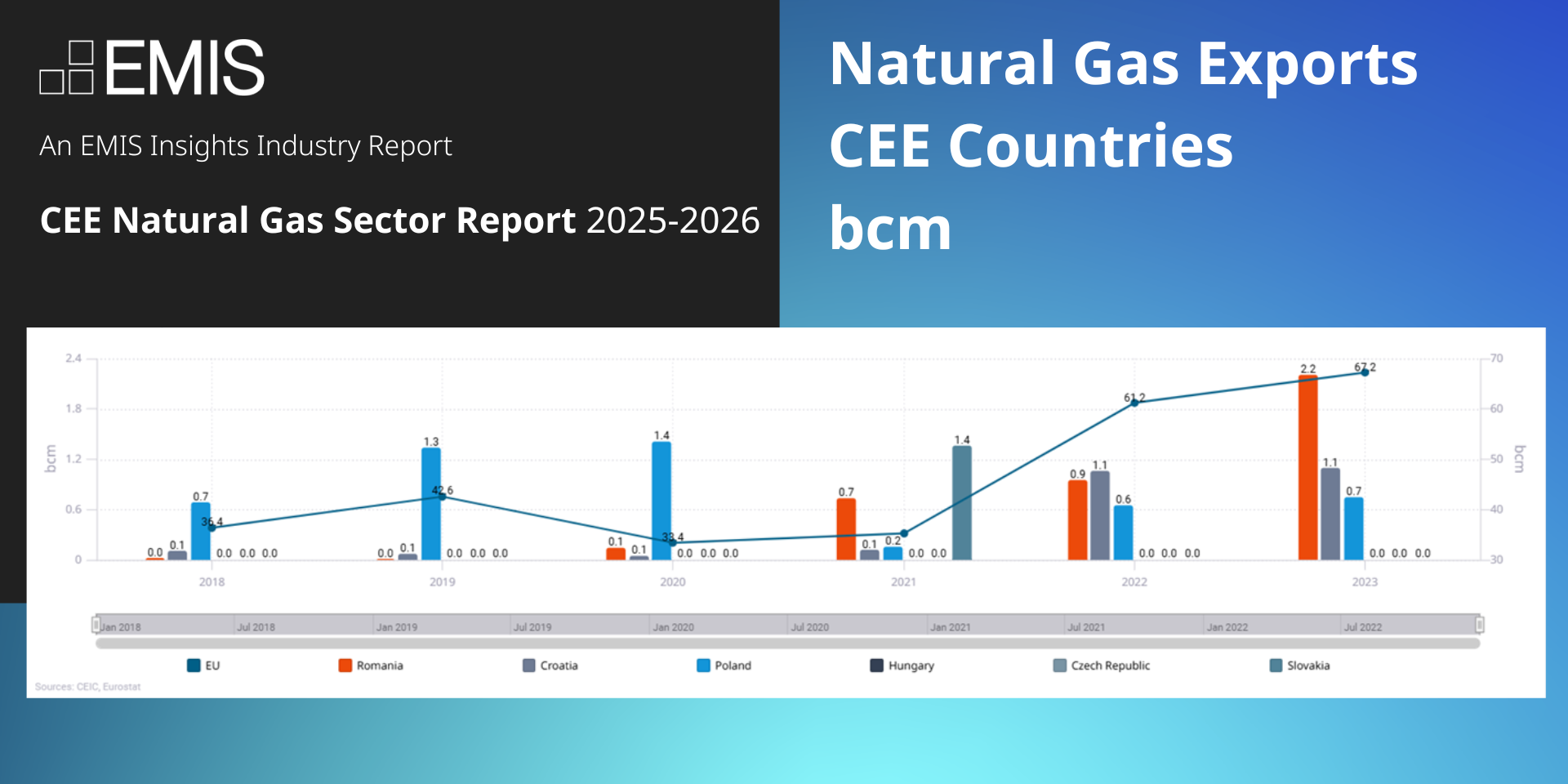

Figure 2. Natural gas exports CEE countries (bcm).

Since the loss of Russian gas deliveries in 2022, Romania, Croatia, and Poland have stepped into new natural gas export roles, as CEE and EU gas trade adapts to LNG imports, reverse-flow capabilities, and diversified sourcing.

The Clean Hydrogen Joint Undertaking has helped draft projects for hydrogen valleys across the EU, including in Poland, Croatia, and Slovakia. /14/ Hydrogen valleys are key nodes in the future corridors because they integrate hydrogen production, storage, transportation, and end-use applications within a defined geographic area, fostering a sustainable hydrogen economy. Construction of the EastGate H2V in Slovakia’s Košice region, for example, started only in April 2025. /15/

According to an October 2024 Bankwatch Network report called ‘Looking Beyond the Hype, Public Funding of Hydrogen in Central and Eastern Europe’, the EU’s cross-border hydrogen infrastructure assumes very high levels of production, consumption, and trade, which may be based on speculative demand scenarios. /16/ Furthermore, green hydrogen is associated with substantial production and efficiency losses, an IRENA publication stated in 2020. /17/

Against this backdrop, the July 16, 2025 publication of Joule magazine makes the case for a more robust European green hydrogen strategy, suggesting raising the 10 million t production target to 25 million t by 2040, given that the EU has not officially committed to a 2040 target yet.18 In February 2025, Daniel Fraile, Chief Policy Officer at Hydrogen Europe highlighted that the EC should not give preference to electrification-only scenarios and should be working towards parallel developping of electricity and hydrogen infrastructure, alluding to a considered scenario of only 3million t hydrogen production by 2030, instead of the 10million t target announced in 2020. /19/

In a July 2025 interview with CEE Energy News, Veronika Vohlídková, executive director of the Czech Hydrogen Technology Platform (HYTEP), said Czechia will not be ready for hydrogen import via pipelines by 2030, so the country’s goal is to develop local production sites. Specifically, the country was considering transforming coal regions into hydrogen hubs, reducing energy dependence on other countries. /20/

According to Vohlídková, the EU rules on green hydrogen production are too strict and are suitable for countries with large renewable energy generation capacities, not Czechia. She also noted that production costs under the current rules make green hydrogen uncompetitive without subsidies. /21/

A similar appeal was launched by German Chancellor Olaf Scholz who, at the beginning of 2025, called on EC President Ursula von der Leyen to modify the excessively strict green hydrogen definition, HydrogenInsight.com reported. /22/

Risk of greenwashing

The EU prioritises the production of certified renewable (green) hydrogen, as it has the highest potential to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. This is allegedly so only if EU member state authorities can make sure the pipelines carrying hydrogen – the smallest molecule – will not leak through microfractures in repurposed pipelines for example. Released into the atmosphere, hydrogen has up to 37 times greater global warming potential compared to carbon dioxide, as it slows down the decomposition of methane. /23/

Nevertheless, green hydrogen – produced via electrolysis using renewable energy such as wind, solar, or hydropower – is considered a good solution for the decarbonisation of carbon-intensive sectors that cannot be feasibly electrified (e.g. steel, cement, chemicals, shipping, transportation, aviation)./24/

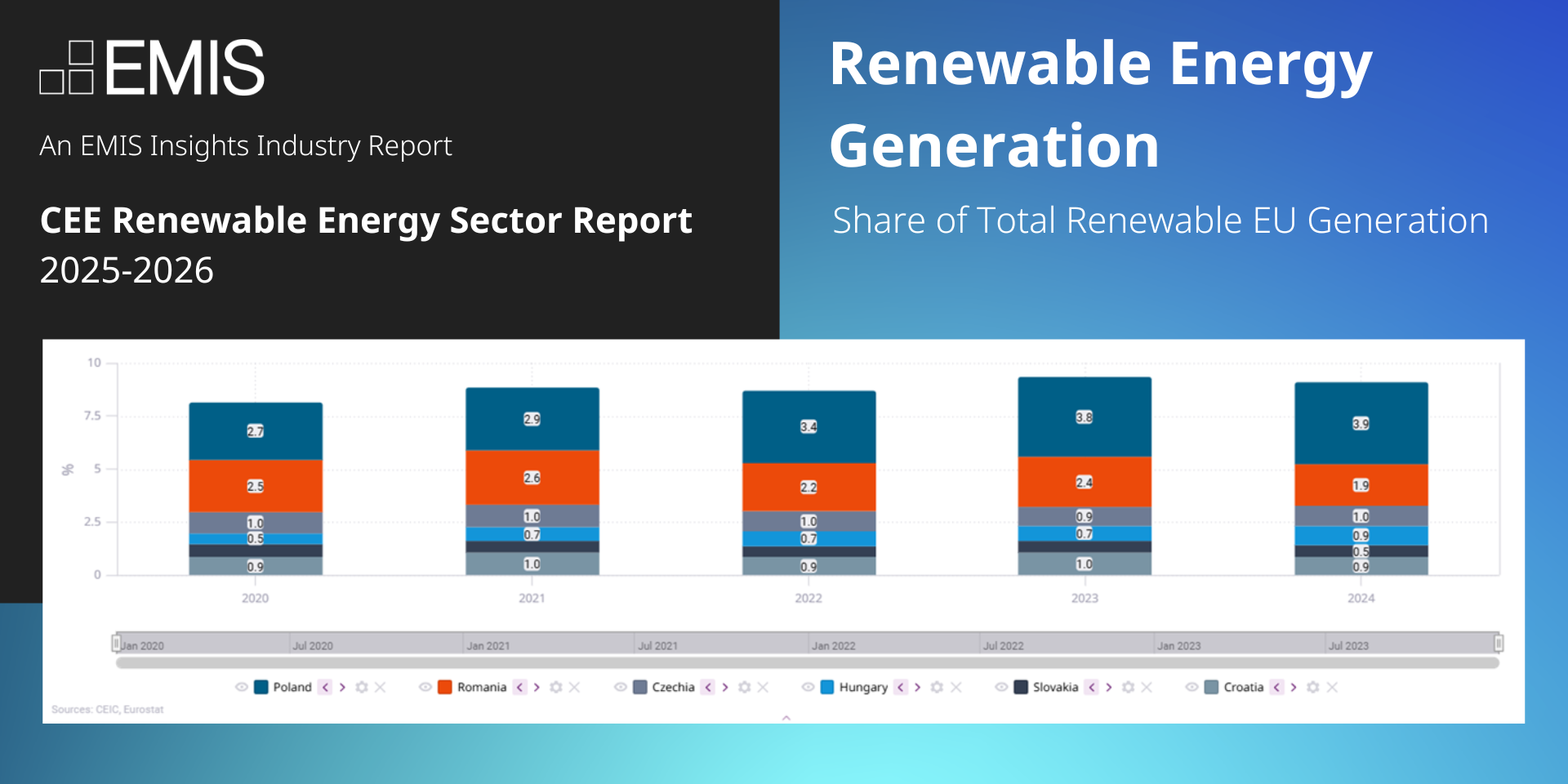

Figure 3. Renewable energy generation in CEE countries (share of total renewable EU generation).

Diverging renewables bases across the CEE region are a key constraint for green hydrogen readiness. Poland and Romania dominate CEE’s renewables generation share, while lower output countries like Croatia, Slovakia, and Czechia, will face greater challenges in meeting EU-certified green hydrogen production targets without rapid renewable capacity growth.

*Are you interested in the full version of the CEE RES report & more insights into the Renewable Sector,

more data, and analysis from the world's fastest-growing markets? >> Explore EMIS

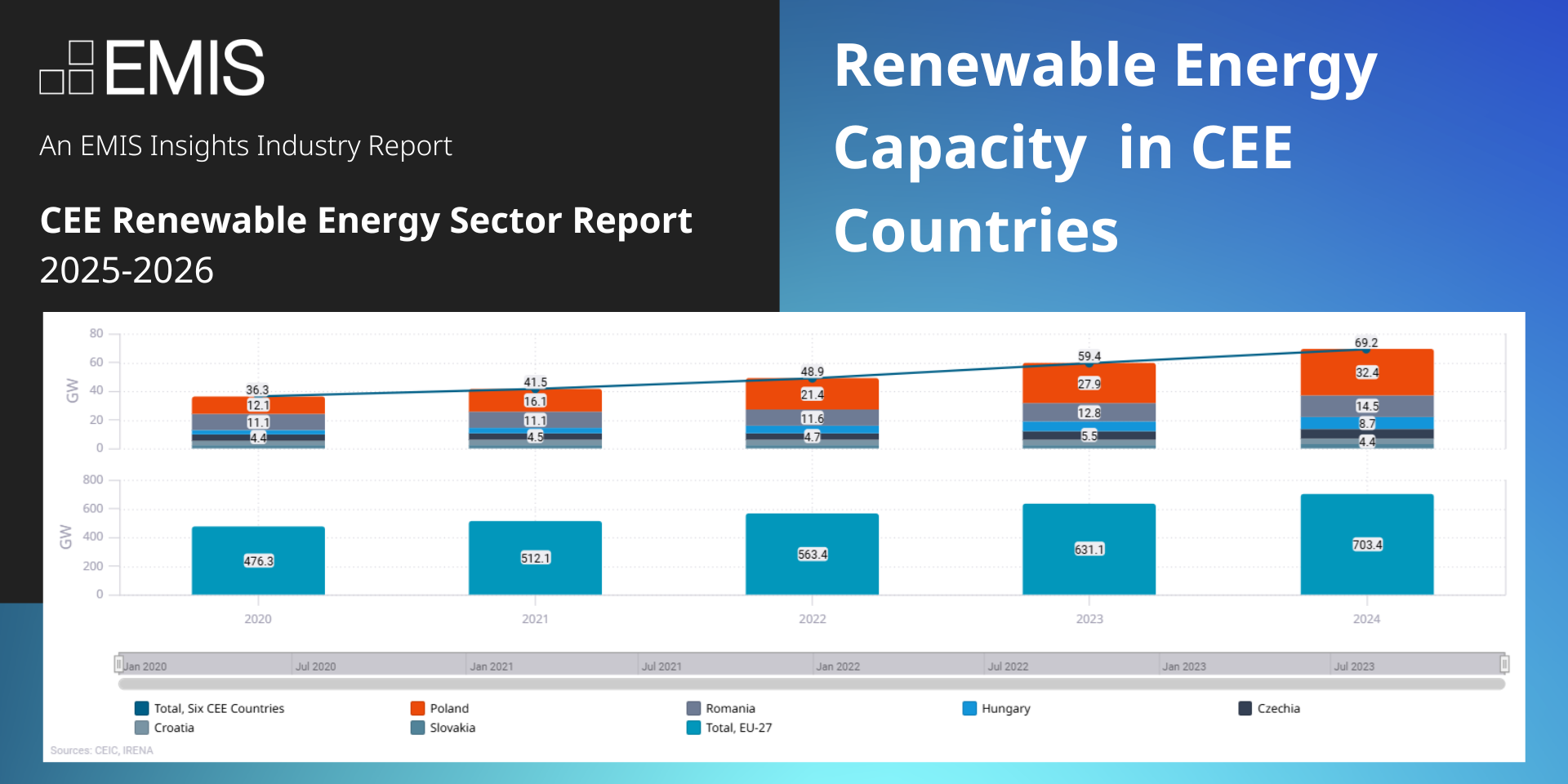

Figure 4. Renewable energy capacity in CEE countries.

Poland boasts the highest renewable energy generation capacity of all CEE countries. This puts the country, in theory, in a good place for renewable hydrogen production, provided it can afford CAPEX costs of €3.81/kg, alongside electricity costs of €3.22/kg, according to 2023 data by the European Hydrogen Observatory.

As much as 96% of hydrogen currently produced in the EU is fossil-based, a February 2025 European Parliament briefing stated. /25/ The EU hydrogen funding framework such as IPCEI and the Hydrogen Bank, allows support for low-carbon hydrogen, which may include blue hydrogen (made from natural gas with carbon capture), and other transitional ‘low-carbon’ forms. /26/

This creates space for ambiguity and greenwashing at the national level, essentially meaning that EU public funds might be used to build fossil hydrogen infrastructure. Another risk is that in the early stages of their functioning, the hydrogen pipelines might carry hydrogen produced with grid electricity that includes fossil fuel inputs. /27/

These concerns are especially valid for the CEE countries where green hydrogen production is immature, national strategies allow grey or blue hydrogen (e.g. Hungary /28/, Poland /29/, Czechia /30/), and certification or enforcement is weak.

As proof of this, not a single EU member state, including none of the CEE countries, has fully transposed the EU’s Renewable Energy Directive III (RED III) by the deadline of 21 May 2025, the EC said on its website in September 2025. /31/ RED III creates a legally backed market demand from sectors like aviation steel or chemicals, mandating that member states use at least 42% renewable hydrogen in industry by 2030 and at least 5.5% of green hydrogen or e-fuels in transportation by 2030. The directive, passed in October 2023, also stipulates that only hydrogen certified under its mechanisms counts towards national targets. However, the document does not fix national targets, creating uncertainty and reluctance from industry to engage in long-term hydrogen contracts, S&P Global said in a June 2025 article. /32/

Without improvements in policy, funding, and demand-side requirements to address high costs and weak demand, less than 20% of the EU’s hydrogen production projects may become operational by 2030, said an April 2025 report by the Westwood Global Energy consultancy titled ‘Europe’s Hydrogen Future: How Much is Realistically Achievable?’ /33/

Storage for flow flexibility

CEE countries have substantial gas storage, /34/ but most of it is not certified or technically fit for (pure) hydrogen storage, which has stricter technical requirements. /35/ CEE countries have been conducting studies estimating the feasibility and safety of converting natural gas storage into hydrogen storage as well as developing new hydrogen storage capacity. For example, in July 2024, Poland announced plans to set up a large-scale hydrogen storage facility in Kosakowo to utilise energy surpluses in Pomerania, CEE Energy News reported. /36/

Poland is EU’s third-largest hydrogen producer by capacity after the Netherlands (second-largest) and Germany (the largest), /37/ so the low level of maturity of its hydrogen storage infrastructure can be used to gauge the general lack of preparedness of the CEE region. Yet CEE should have operational hydrogen storage infrastructure well ahead of the 2030 deadline, if storage specifications are to be consistent with a gradual transition from blended to pure hydrogen. To help address this, the Annual Work Programme 2025 of the Clean Hydrogen Joint Undertaking has stated it will invest in development of lined rock caverns for hydrogen storage alongside other infrastructure vital for enabling cross-border hydrogen flows and storage trials. /38/

Read the entire Article via World Pipelines, page 17

Note: For references, please refer to the above page of the original article.

*Are you interested in the full versions of the EMIS reports & more sectoral insights, more data, and analysis from the world's fastest-growing markets? >> Explore EMIS